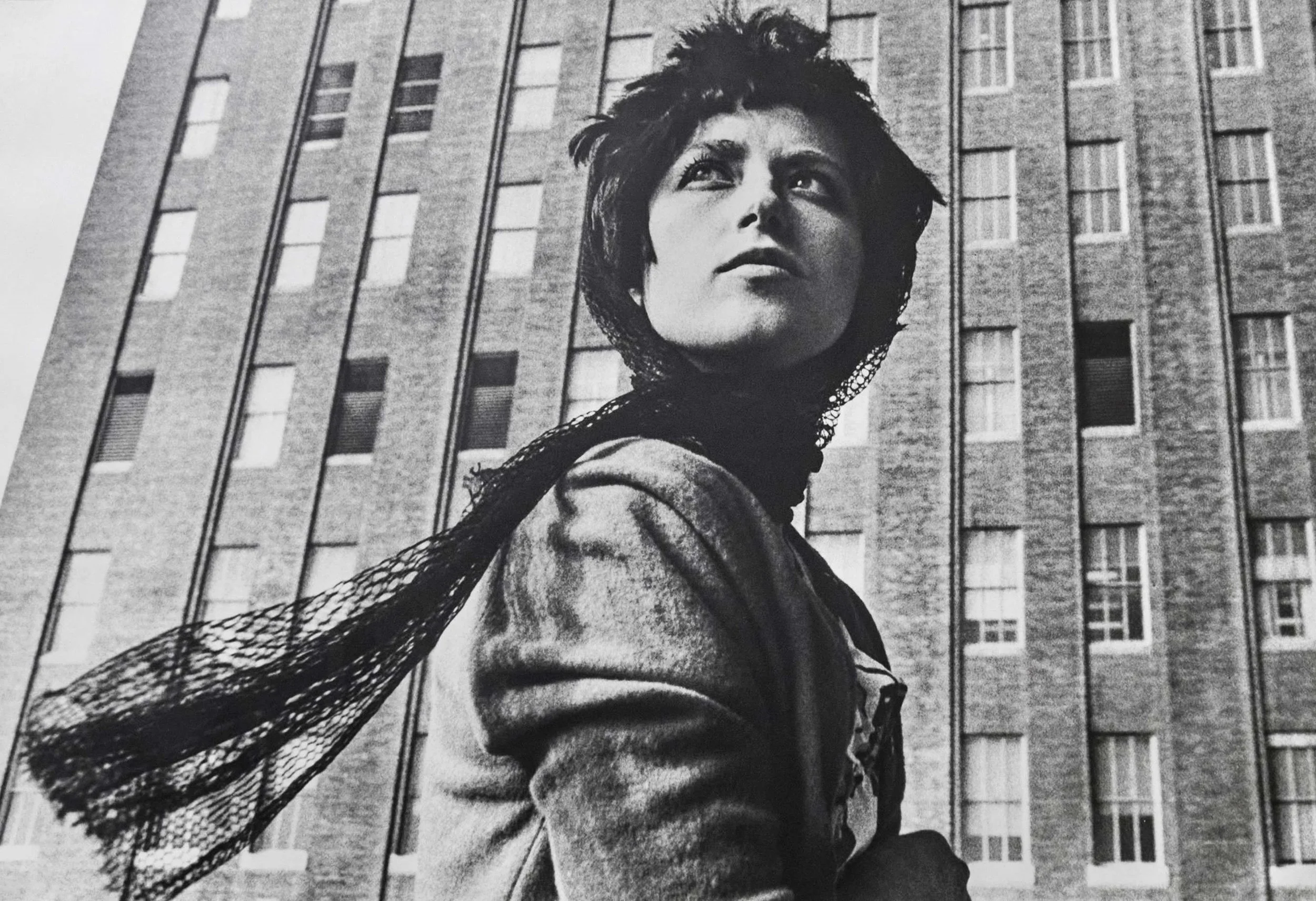

Cindy Sherman

Untitled Film Still #58

1980

Gelatin silver print

Growing up in Huntington Beach, Long Island, Cindy Sherman loved television and movies from an early age. She has fond memories of watching Hitchcock’s Rear Window and other classics on WOR-TV Channel 9’s Million Dollar Movie program that showed the same film every night for a week. She was a creative child who drew constantly and spent a lot of time playing dress-up, reinventing herself as an old lady, a witch, or a monster rather than a princess or ballerina (or any more typical imaginings of little girls). She did well in art class at school, going on to earn her BA from Buffalo State College in 1976. At college she studied drawing, painting, and photography, and experimented with costumes and performance art, attending parties dressed as Lucille Ball for example, and photographing the results. She usually dressed up as women, enjoying the myriad possibilities of wigs, fashion, and make up; she found male personas too limiting.

Sherman moved to New York City in 1977, and got a job as a receptionist at the non-profit Artists Space downtown. She went to work in costume occasionally, arriving dressed as a nurse, or a 1950s-era secretary. That fall, she photographed the first group of the series for which she has become widely known, the Untitled Film Stills. Inspired by the stylized aesthetic of directors like Hitchcock and Antonioni, Sherman created images in which women and their mise en scène appeared enigmatic – never smiling, rarely crying, mysterious. Each of the seventy Film Stills is a photograph of the artist herself, disguised as a stereotypical female movie character, generic but familiar from tropes of film: ingenue, big-city career girl, vamp, housefrau and more. Even characters that deliberately echo cinematic icons like Brigitte Bardot or Sophia Loren remain one step removed – a Bardot “type” but not a Bardot portrayal. The Film Stills never recreate or refer to real films; they are archetypes. Sherman’s photographs are all untitled to further embrace ambiguity; even her title numbering system is intentionally slightly out of order. The artist’s investigation of women’s identities is both personal – she is in every picture – and universal. Women’s roles have been culturally prescribed since society began, but Sherman upends normative stereotypes with deft re-envisioning.